Depression comes in many different forms and can affect people in different ways. The causes of depression can vary, as can the symptoms. The symptoms are wide-ranging and while most people recognise that depression can cause intense sadness, a lack of energy and anxiety, there are a number of symptoms that people are less aware of.

The importance of recognising all symptoms of depression

Depression not only affects how a person thinks and feels. This mental health condition can cause physical symptoms and can also impact on behaviour.

When people know what to look for, it can help them to get access to the right help and support faster. Dr Syed Omair Ahmed says: “When a person continues to live with depression unknowingly and without accessing the right treatment, it can cause their depression symptoms to worsen and serious health issues can arise.

“It can lead to physical health issues, including malnutrition, obesity, heart disease and diabetes. If a person turns to alcohol or drugs in an attempt to alleviate their symptoms, this can cause further issues. People can also develop cognitive decline and suicide risk also increases with severe depression. Psychotic symptoms can also develop.

“Family life can become adversely affected, and relationships break down. Some people also engage in reckless behaviour which can get them in trouble with the law.”

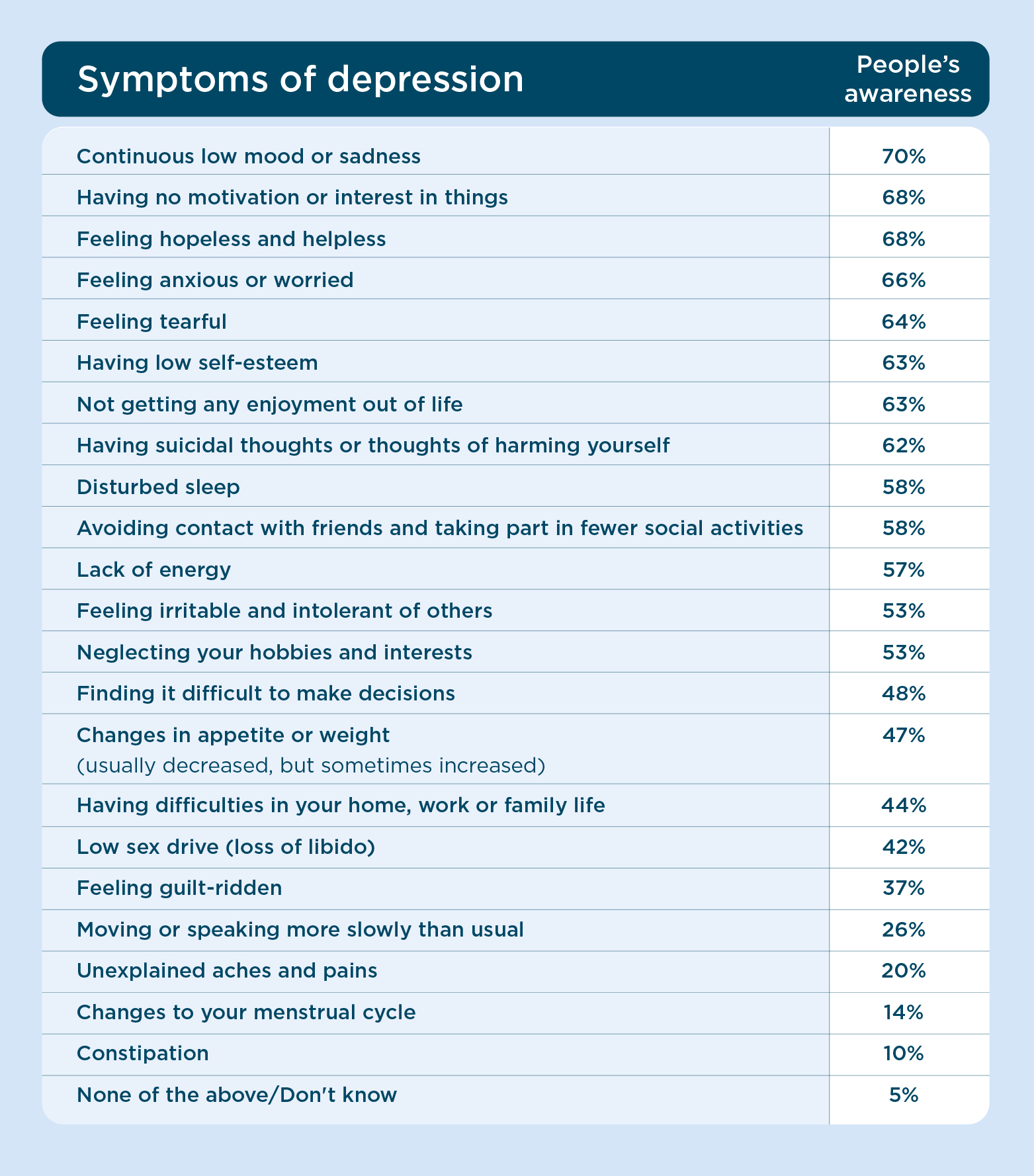

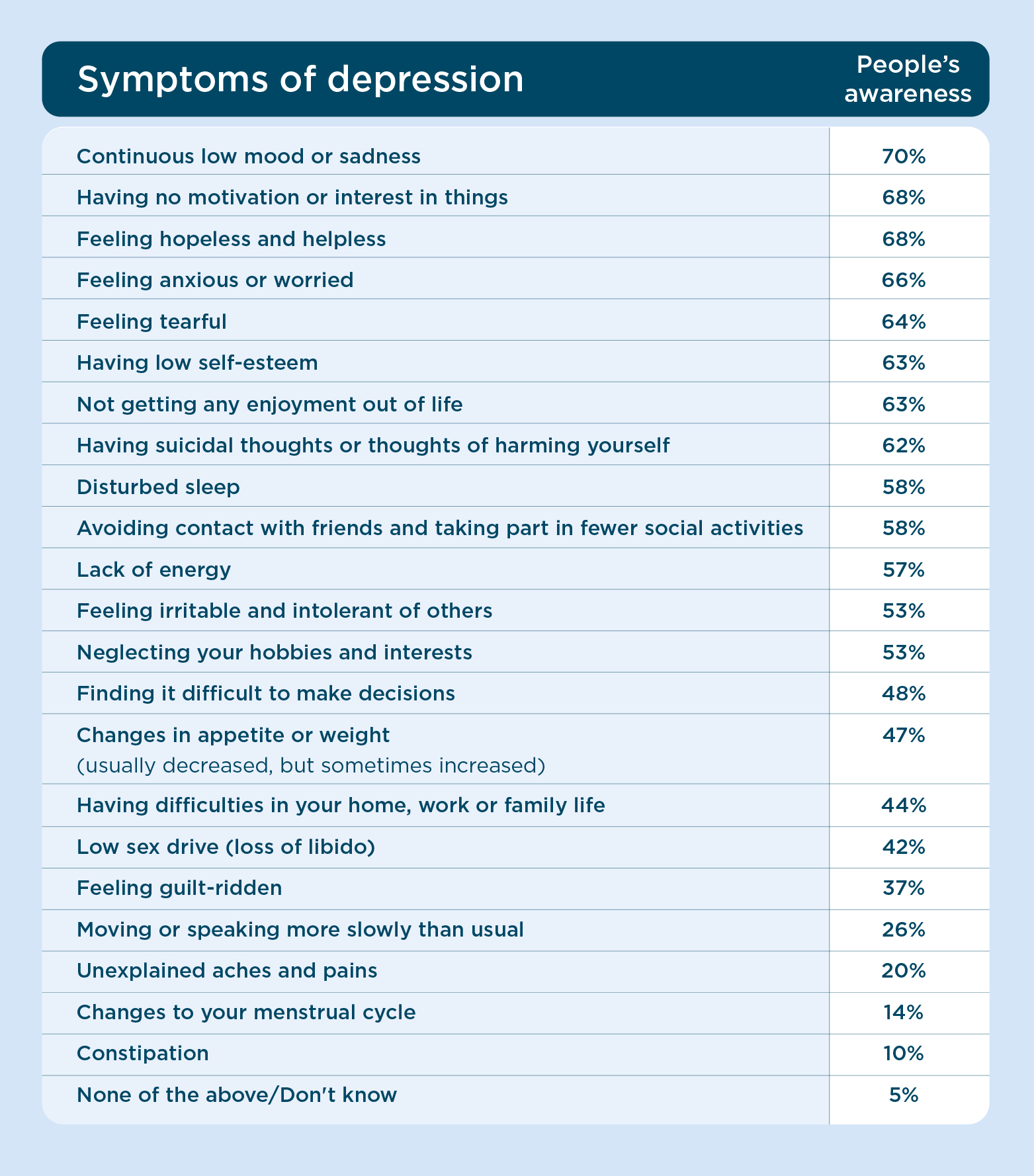

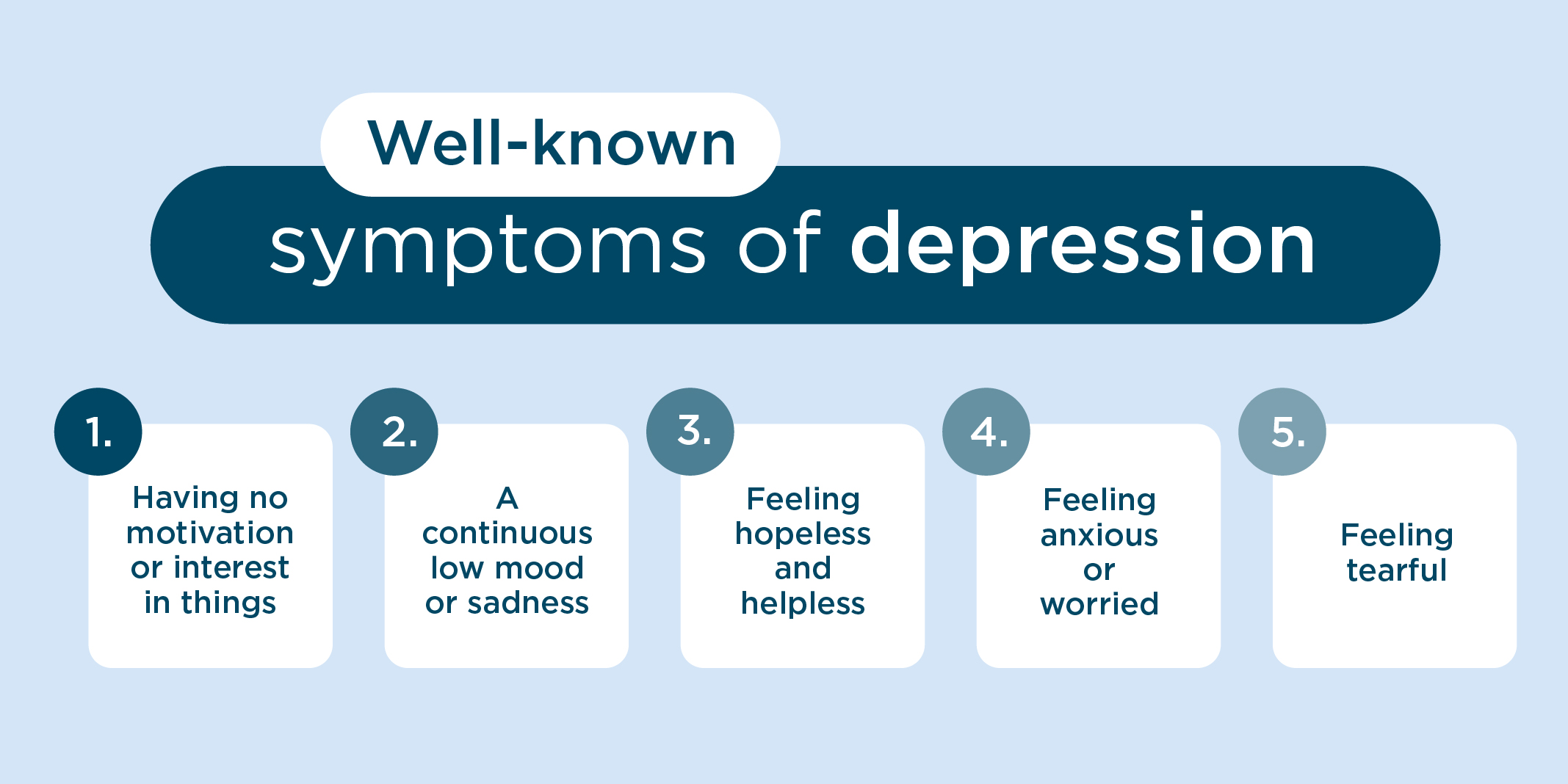

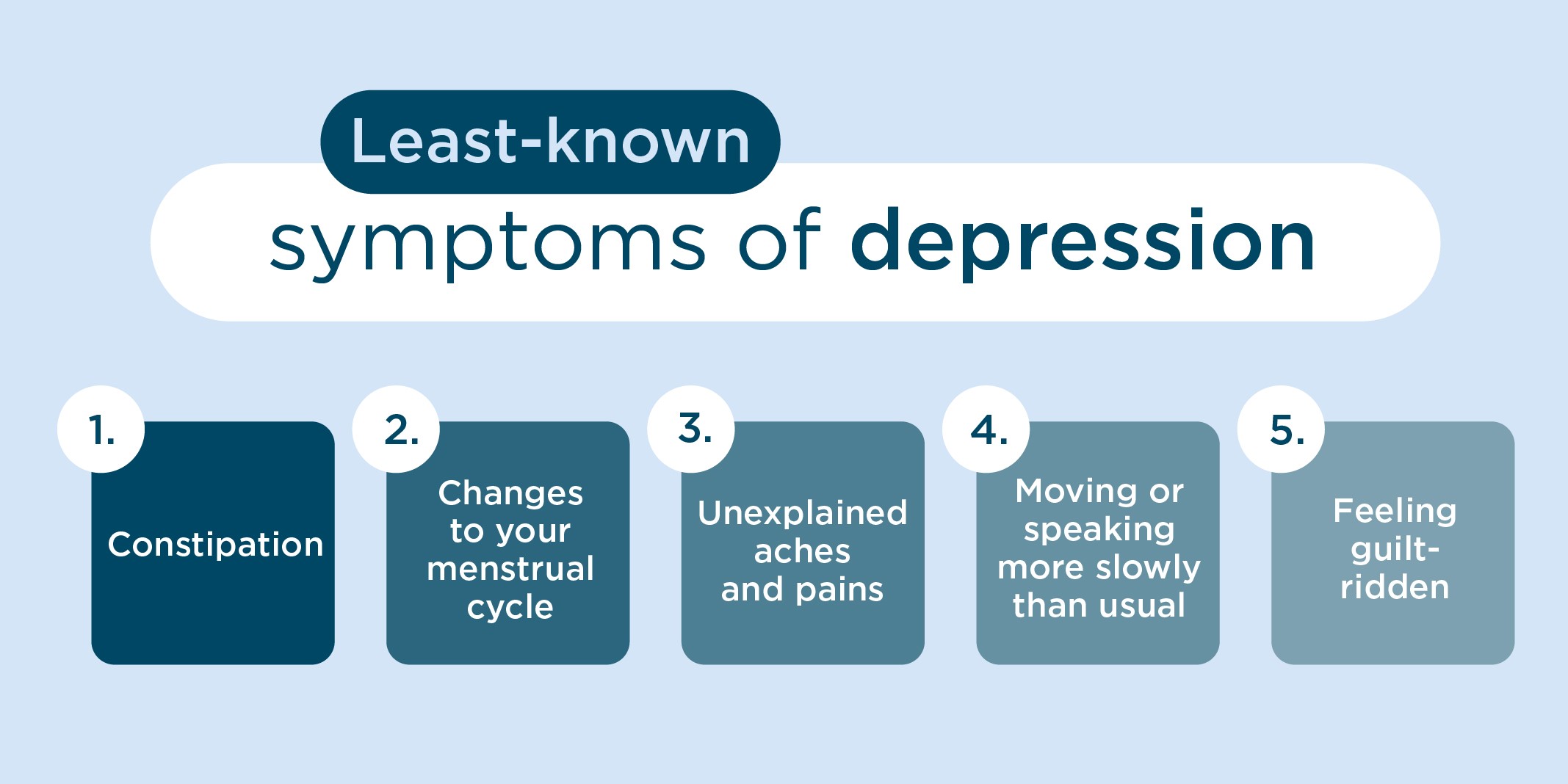

We recently ran a survey to find out people’s understanding of the different symptoms of depression. These were the results:

The most well-known symptoms of depression included:

And, the symptoms of depression that people were least aware of were:

Understanding the lesser known symptoms of depression

Dr Ahmed has put together information on the lesser known symptoms of depression and why they can happen:

- Finding it difficult to make decisions - depression can decrease the volume of certain areas of the brain and disrupt normal ‘electrical connections’. This can cause a person’s focus and concentration to diminish, making it difficult for them to make decisions. Depression also leads to sleep disruption and lethargy. This lack of energy can affect a person’s ability to make decisions

- Changes in appetite or weight - depression can change our metabolic systems, which can lead to an increased or decreased appetite. As people with depression can have lower energy levels, they may also be less motivated to prepare food. On the other hand, some people may ‘comfort eat' as a coping mechanism

- Having difficulties in your home, work or family life – a loss of sleep caused by depression can cause some people to become irritable, which can affect those they're close to. A person may also withdraw from others, which can impact relationships. Problems with focus and concentration may also cause work performance to decline, and lead to a demotion or job loss. If a person resorts to self-medicating with alcohol or drugs, this can also exacerbate difficulties at home, work or within the family

- Low sex drive - people with depression can experience a loss of desire and experience delayed orgasm. A person’s sexual arousal depends on their ability to experience pleasure. If this is missing due to depression, this can lower their sex drive. Low energy levels and low self-esteem also contribute to this picture

- Feeling guilt-ridden - people with depression struggle to achieve perspective on negative life events. This can make them feel wholly responsible for negative things that happen, making them feel guilty

- Moving or speaking more slowly than usual – the slowing of thought processes and physical movements is a well-established symptom of severe depression. Partly due to decreased energy levels, it's also understood that certain chemical and structural changes in the brain can cause this

- Unexplained aches and pains - people with depression often experience various body ailments, including pain. While quite often there'll be no underlying physical cause, the pain and distress is very real. In depression, as emotions aren't processed properly, people tend to focus on the physical symptoms they experience rather than underlying emotional problems

- Changes to your menstrual cycle - during a depressive phase, a hormone called cortisol rises. This sends messages to the brain and the reproductive system, delaying or ceasing ovulation, leading to a delayed or absent period

- Constipation - if a person’s appetite is adversely affected, and their dietary intake is quite poor, they may lack essential nutrients and fibre. This can lead to bowel disturbances, including constipation. Low fluid intake can also worsen constipation. Low serotonin levels in depression have also been shown to slow gut movements

What to do if you think you’re suffering from depression

If you're concerned that you may be suffering from depression, speak to friends or family, as they'll be an invaluable source of support.

Also, book an appointment to visit your GP, who will be able to provide you with a diagnosis and a treatment programme to follow. This may include psychological therapy, medication or a referral to a specialist mental health service like Priory.

If you're worried you may have depression, you can also come directly to Priory. One of our consultant psychiatrists will be able to assess your symptoms, provide you with a diagnosis and recommend the best form of depression treatment for you to receive at one of our hospitals or wellbeing centres. This could include:

- Weekly counselling or talking therapy sessions – accessing therapy, especially cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), can often be useful for people with depression. These sessions can help you to determine the thoughts and feelings that are fuelling your depression, and help you to work on moving beyond them so they have less of a hold on you

- Day sessions at one of our hospitals and wellbeing centres – a form of treatment that's slightly more intensive than weekly therapy, attending day or half-day sessions at one of our hospitals and wellbeing centres will see you taking part in a programme that includes both group and one-to-one therapy as well as wellbeing and mindfulness sessions

- Residential hospital stays – for people with severe depression, your consultant psychiatrist may recommend a more intensive form of treatment, which can include a stay in one of our hospitals. During this time, you'll receive 24-hour care and support, and take part in a structured programme that includes both therapy and wellbeing sessions

- Medication – if appropriate, your consultant psychiatrist will be able to prescribe medication alongside therapeutic support

In addition, a treatment approach known as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is available at our Harley Street Wellbeing Centre. This uses electro-magnetic fields to stimulate areas of the brain associated with mood control, and is typically used to help people with treatment-resistant depression.